In the latest edition of AM magazine David Francis takes deep-dive into the UK's new car registrations and asks: "Has the market finally reached 'peak premium?'"

October registrations (up 26.4%) looked positive but, in reality, that figure only brought them back to where they had been in 2020 – itself hardly a great period for car sales.

This has led the Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders (SMMT) to downgrade its 2022 full year forecast to 1.57 million – the lowest level since 1982.

Put another way, we have lost 40 years’ market growth.

Of course, a fair proportion of the fall is down to the chip shortage. Europe is expected to lose production of 1.5 million cars in 2022, out of a global total of 4.2 million.

Production of automotive chips is forecast by Alix Partners to rise by 20% next year, but the big question is whether that will be enough.

In some ways, the industry hopes that it will not. If a 20% increase is sufficient to meet demand, then the industry is in a deep recession.

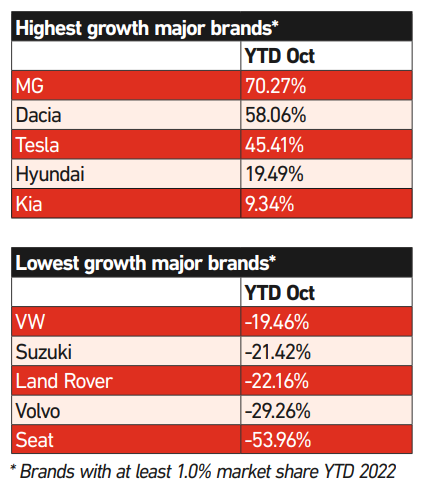

Back in the present, Ford is slightly out-performing the market, and has marginally extended its lead over VW.

Back in the present, Ford is slightly out-performing the market, and has marginally extended its lead over VW.

Of course, this development has been overshadowed by the news that, after 46 years and a global production run of 16 million, the Fiesta will be dropped in 2023.

The Focus will not be far behind, as Ford moves to VW platforms for small and medium models.

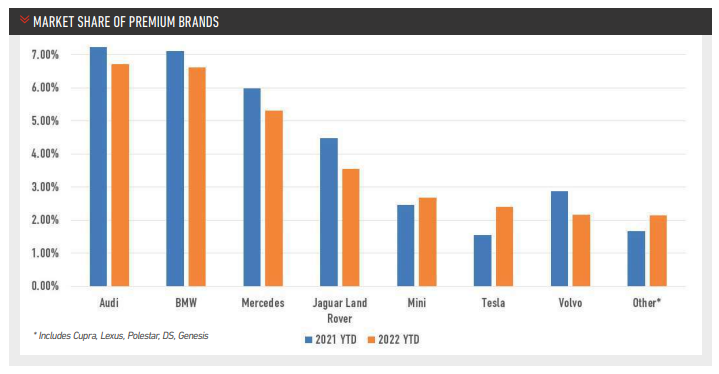

PREMIUM BRAND DECLINE

Behind VW, there is a huge battle for third place. No fewer than four manufacturers (Audi, Kia, BMW and Toyota) have a market share of between 6.5% and 6.7%, with fewer than 3,000 units separating them.

Kia is the only one of the four manufacturers to have increased sales year-to-date (YTD), so could be in a good position to finish in third place if it can maintain its momentum.

Of the rest of the Top 10, the company with the most mixed feelings is probably Nissan. It has the UK’s best-seller YTD in the Qashqai, but is only tenth overall.

All its other existing models have fallen by more than the overall market, so it needs the new Ariya to make a big impact if it is going to get back to the 5%-6% share it used to enjoy.

Looking at the other end of the sales chart for a change, a couple of the biggest losers have been companies that, a while ago, might have been expected to have benefitted from the SUV boom.

Jeep, which was a big presence in the 1990s with the Cherokee, has seen yet another market share collapse. It has sold only 2,200 cars this year (down 48.7%) for a market share of just 0.16%.

Similarly, Subaru, once the go-to brand for rural vets and people living at the end of farm tracks, is down by 40.2% to a market share of just 0.08%.

To put it another way, Subaru sells approximately the same number of cars in the UK (1,056 YTD) as Ferrari (879 YTD).

It is hard to see how selling such small volumes of relatively inexpensive cars can be commercially viable.

If Jeep and Subaru are to remain in the UK, they need to come up with something pretty radical after more than a decade of steady declines.

Overall, the most notable trend among manufacturers is the decline in market share of premium brands after decades of inexorable growth (see table).

Overall, the most notable trend among manufacturers is the decline in market share of premium brands after decades of inexorable growth (see table).

First, we should establish what we mean by premium. We would define it as a manufacturer within mainstream segments that offers a more prestigious brand, so Land Rover would be in (the Evoque is an alternative to a Kuga), but Porsche would be out (the Macan is a segment higher).

Overall market share of premium brands has slipped from 33.4% to 31.6%, and would have fallen further, but for the sharp rise in Tesla sales.

VALUE BRAND GROWTH

At the same time, market share of the two true value brands on the market (MG and Dacia) has jumped from 2.8% to 4.9%.

Brands such as Škoda and Kia were value brands once, but have long-since joined the mainstream – indeed they would both claim that they are positioned above some traditionally mainstream brands.

While it is always dangerous to take a couple of data points and extrapolate a trend, there does seem to be something interesting at work.

Electrification inevitably makes cars more expensive, and people’s real incomes are falling, so something has to give.

Electrification inevitably makes cars more expensive, and people’s real incomes are falling, so something has to give.

Dacia is offering a low-cost alternative to electrification (at least for now), while MG is offering EVs at close to petrol car prices.

It would be rash to assume that premium cars are now in decline, but it would not be unreasonable to think that their days of relentless growth may be over.

By definition, premium is a relative term, so premium models cannot become the majority of the market.

Taking approximately one-third of the market may be something of a natural ceiling. The same logic seems to have occurred to BMW and Mercedes-Benz who say they will progressively reduce their presence in smaller cars (e.g. Mercedes will drop the A- and B-Class). Have we now reached “peak premium”?

Attention is now turning to what we can expect in 2023.

The aforementioned chip shortage will still constrain supply, but the bigger worry is the level of demand.

“Unprecedented” is possibly the most over-used word of the past three years, but it is hard to avoid in the context of the fall in household disposable incomes.

According to the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) the average person will see their income fall by 2.2% in the year to April 2023, the worst dip since records began in 1956.

In such circumstances, a new car may be a long way down the list of priorities for many.

The SMMT is forecasting a market of 1.8 million for 2023: to put that into context, the average for the five years from 2013 to 2017 was 2.5 million, and 1.8 million was the figure for 1993, as we started to come out of the early 1990s recession.

Login to comment

Comments

No comments have been made yet.