With the exception of Brexit, hanging over the market like a malevolent storm-cloud, the biggest issue facing the UK car industry in 2019 has been electrification. The issue of climate change has shot up the political agenda, and the question of electric vehicles has shifted from “if?” to “when?”.

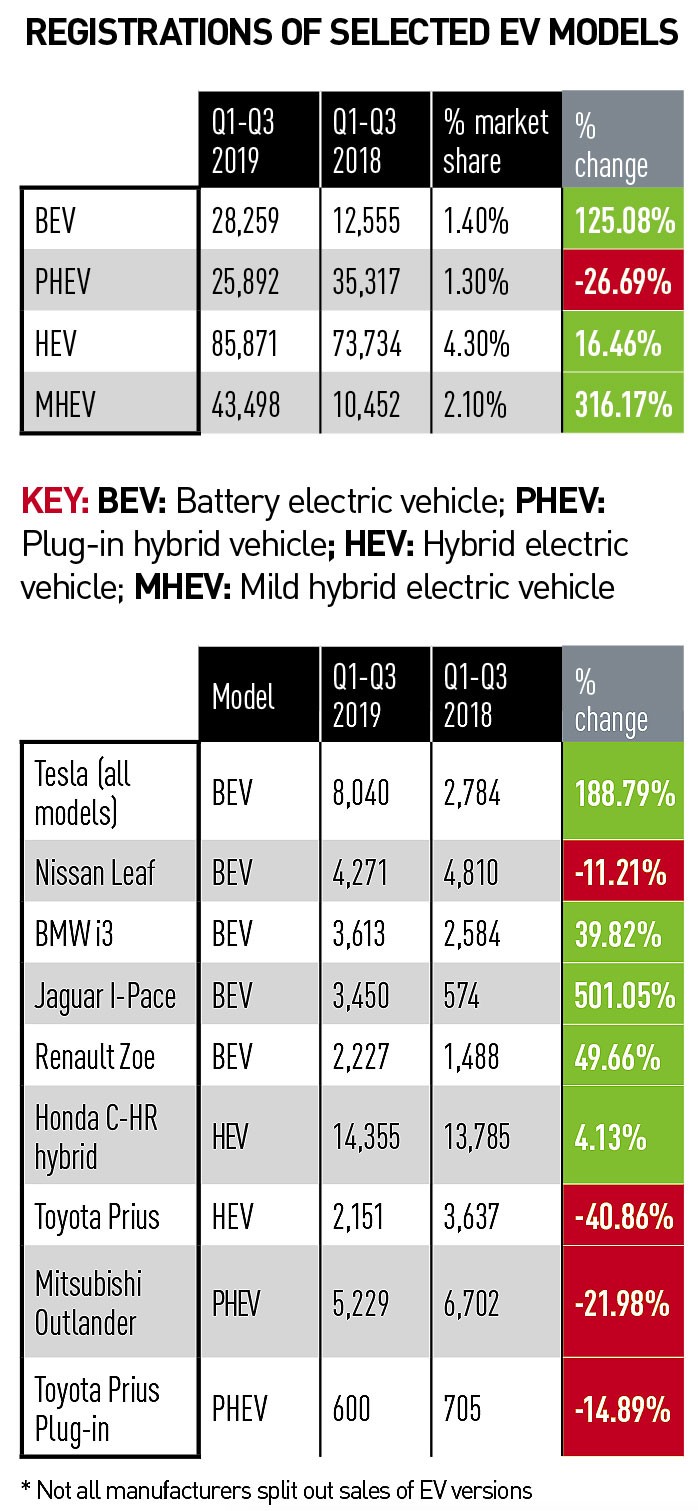

Looking at the market data, it would seem that the flood of EVs is still some way off, but we are now seeing the first cracks in the dam. Market share of battery electric vehicles (BEVs) increased by 125% YTD (see table, right), although a cynic might say that 125% of nothing is still not very much. Hybrid sales are also increasing steadily, but plug-in hybrid sales have temporarily faltered since the Government decided too many of them were being bought as a tax-dodge, and were not actually being plugged in.

The first issue to address with hybrids is to establish what sort of hybrids we are talking about. There are broadly five types (see below): micro, mild, full, plug-in and range-extender. Over the next 10 years, all petrol and diesel engines will move to some form of electrification – micro at the very least, but most will have mild hybridisation at a minimum. From 2021, virtually all new petrol and diesel premium models will be mild hybrids, and the technology will steadily move down to the rest of the market.

Most independent forecasters (e.g. Ricardo Consulting) expect that, by 2025, of the three main types of electric drive, battery electric vehicles (e.g. Nissan Leaf) will account for about 60% of the total, plug-in hybrids about 30% and full hybrids only about 10%. That would seem logical – as the cost of batteries falls, one would expect cars to use larger batteries. It seems unlikely manufacturers will go to all the cost of engineering a hybrid drive system in 2025 and then use a small, non-plug-in battery to power it, when larger batteries cost very little more.

Most independent forecasters (e.g. Ricardo Consulting) expect that, by 2025, of the three main types of electric drive, battery electric vehicles (e.g. Nissan Leaf) will account for about 60% of the total, plug-in hybrids about 30% and full hybrids only about 10%. That would seem logical – as the cost of batteries falls, one would expect cars to use larger batteries. It seems unlikely manufacturers will go to all the cost of engineering a hybrid drive system in 2025 and then use a small, non-plug-in battery to power it, when larger batteries cost very little more.

Even in today’s market, where batteries are still quite expensive, hybrids are not doing as well as manufacturers might have hoped. Toyota planned to reap the benefit of being the first manufacturer to embrace hybrid technology – indeed at one point, “Prius” was synonymous with “hybrid”. However, as hybrid technology moves from being mysterious witchcraft to standard fitment, the idea of a separate bodystyle is looking rather quaint. It is as if a manufacturer decided to create a different bodystyle for a turbocharged engine. Prius sales fell by 36.6% YTD, and are now behind both the Nissan Leaf and BMW i3, with fewer than 3,000 registered.

The question of designing a different bodystyle for a battery electric vehicle (BEV) is more complex, for two reasons. Firstly, a BEV is a lot more radical than a petrol hybrid and, secondly, there are sound engineering reasons for creating a different platform. The most efficient way to position batteries is within the floorpan between the axles. That means the traditional engine compartment is no longer needed, and the proportions of the body can be very different (e.g. the short-nose, long-cabin look of the Jaguar I-Pace). An electric version of a conventional bodyshell (e.g. Peugeot 208) is never going to be as space-efficient, as it will have to cater for two powertrains with very different shapes. However, it will be a great deal cheaper to make a single body – the jury is still out on which approach works best. The 2020 Honda-e, with its cute, bespoke platform, will be an interesting case study.

The most important new BEV will undoubtedly be the VW ID3 – so-called because it is meant to be the third model that will define VW after the Beetle and Golf. VW has put a huge stake in the ground, proclaiming that it intends to make Europe’s definitive electric family car. So how many can it expect to sell?

The UK Government wants the share of electric vehicles to be 50% by 2030. It should be noted that the Government classifies electric vehicle as a car with an electric range of approximately 100km (its “Road to Zero” strategy is vague on the precise distance), so a plug-in or range extender hybrid would count towards the target. Most in the industry do not expect pure BEV to get much beyond 30% market share by 2030.

To put that into perspective, the crossover/SUV bodystyle (taking everything from a Ford Ecosport to a Range Rover) accounts for 41% of total sales – and every mainstream car manufacturer now has a range of crossover models. Hence, every manufacturer will have a range of BEVs within 10 years, even if they do not represent the majority of sales.

Coming back to the more immediate future, hybrids have the smallest growth potential. In 2019, sales only went up by 16.5%, despite the tax changes that increased their attractiveness compared with plug-in hybrids. Both Toyota and Honda are presenting petrol hybrids as the sensible alternative to diesel engines, an argument that has some merit. However, hybrids are something of a “bridge technology” to get us to plug-in hybrids.

When it comes to BEVs, 2020 is likely to be the year electric vehicles start to go mainstream. Both Tesla and Jaguar have demonstrated that BEVs can take a significant share of premium car sales. Next year, models such as the VW ID3 can achieve worthwhile volumes in the mass market. Rather sadly for Nissan, there seems to be no dividend for pioneers. Leaf sales fell this year, and rumours from within Nissan say they expect to sell fewer again next year as competition intensifies. As ever, the car market is an unforgiving place – you are only as good as your most recent model. DAVID FRANCIS

Login to comment

Comments

No comments have been made yet.