The announcement that the UK government is bringing forward the final date for the sale of fossil fuel powered vehicles to 2035 is without a doubt a laudable commitment.

However, the journey to emission-free vehicles is perhaps less simple than the government actually appreciates, and if the belief is there that the industry and the economy can cope with such a rapid transition then there must be a grand plan yet to be revealed that will change the timescale that currently appears to be a fantasy.

As the situation now stands, there are 32.5 million cars on UK roads.

These are roughly split 14m diesel, 18M petrol, 0.5m hybrid and EV (EVs accounting for only 155,000 cars on UK roads).

The Government has committed to only allowing EV new cars from 2035 – not even hybrids – but is this huge commitment actually doable?

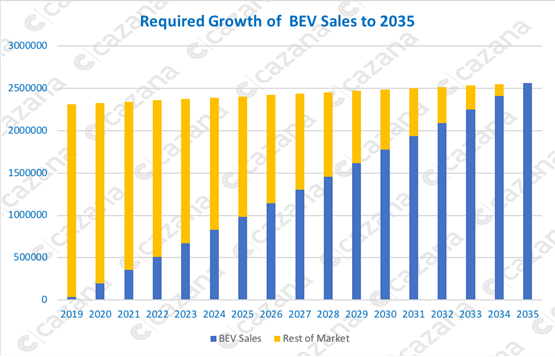

In 2019 sales of BEV’s saw the highest-level market penetration to date at 37,850 cars in the UK which was 1.6% of the 2,311,140 cars sold. Fuel Cell vehicle sales were negligible. The chart below demonstrates the journey ahead:

This chart assumes a total vehicle sales growth of 11% over the next 15 years and simply plots the rate of growth required on a linear basis to achieve the government goal.

This chart assumes a total vehicle sales growth of 11% over the next 15 years and simply plots the rate of growth required on a linear basis to achieve the government goal.

This representation of the market transition does not account for some huge obstacles that lie in the path of the UK automotive industry and economy overall.

Some very basic essentials need to be provided to be able to start the journey in earnest, the first of which is the development of the charging infrastructure that whilst improving swiftly is woefully short of current requirements.

The thought of adding another 195,000 vehicles into the equation during 2020 alone is challenging at best.

Other variables include how the charging issue in towns and cities will work where multiple occupancy buildings are increasing and space for charging points is very limited.

Move a few years further along and the pressure on the national grid will be immense and recent research has indicated that the power suppliers will not be able to cope with increase in power demand with the current electricity production facilities.

Couple these key issues with the fact that the UK consumer is still not convinced by BEV or Fuel Cell cars and the dealer networks still not comfortable with selling them and the task looks ore unachievable.

Consider the impact on workshops that will need to rapidly change service and maintenance offerings, the migration of the current fuel supply change to a new business model.

Not to mention the sea change required for the contract hire and leasing industry and the finance companies that need to be able to make these cars affordable to the consumer.

Accepting that the true rate of sales increase will not be linear there are some large hurdles to be dealt with in the immediate future.

EU targets are already forcing OEMs such as Fiat Chrysler to offset the overall brand emission targets by purchasing emission ‘tokens’ from Tesla to minimise emissions fines.

The consumer is actually buying larger cars with worse CO2. There appears to be a mismatch between public outcry of pollution issues and what cars people actually want to own/be seen in. Increasing popularity of SUVs is largely responsible for this.

Government’s plug-in car grant (PCIG) for EVs was £4,500, now down to £3,500 per new car. It is safe to assume this incentive will continue to drop as we approach mass adoption.

Roadmap to 2035

In order to reach a production level of 2m EVs, OEMs will need to ramp up from the current rate of 38,000 EVs in 2019.

If we assume a linear ramp up, OEMs will need to create over 17m EVs in that time – a huge and hugely unrealistic total considering the current EV production rates.

Such a total would also mean that over half of all cars on the road by 2035 would be EVs which, whilst in many ways is an appealing by-product of such high volumes of EV production, it doesn’t appear to be realistic – just think of the infrastructure changes needed to support UK vehicle usage if more than half of the cars were EVs within 15 years.

Even if we plot a more realistic exponential curve to hit an eventual 2m production by 2035, the total EVs produced still exceeds 10m cars.

Which suggests that the problem will not only be how OEMs scale-up to build this huge quantity of new cars (that’s roughly the entire current annual production of combustion-engined cars built by the Volkswagen Group), but also how the UK Government plans to support the rollout of the crucial infrastructure.

As EV volumes hit tipping point, you can be sure the UK Government will have to find new ways to tax them.

Some new vehicle tax measures will surely be needed to recapture the £28.4 billion that fuel duty raised in 2019.

So while the promise of EVs is currently nearly free motoring, the UK Government probably can’t survive with that being the future at scale.

Fuel duty costs currently equate to roughly £1,000 per household – a hugely useful source of cash.

It simply isn’t feasible to assume that they would allow EV usage to totally eradicate this.

But if they were to place a levy on EV usage there would be an outcry from the consumer and environmentalists.

Summary

Reaching pure EV production in UK by 2035 means roughly 10m EVs on the road, assuming a conservative growth in EVs over the next 15 years.

The UK government commitment places huge pressure not only on OEM new-technology production ramp-up rates (to a level never before seen) and also asks some huge questions of the Government’s own commitment to deploying a viable charging infrastructure.

There also remains a huge hole in government fuel duty that must be recaptured somehow from EV drivers.

One thing’s for sure, the vehicle retail marketplace will become increasingly volatile, as the value and long-term attractiveness of EVs plays out.

Some other market parallels can be used here – for example the rollout of the car itself when it replaced the horse 100 years ago.

Horses did not become extinct- they merely moved from primarily a transportation role to that of competition and pleasure.

We expect a similar future for the humble petrol/diesel car. The best of breed will become treasured items. The more mundane will quickly become forgotten.

Authors: Cazana valuations director, Rupert Pontin, and Tom Lawrie-Fussey, Cazana's global automotive lead

PCA - 05/02/2020 16:19

By 2029 Self driving electric cars will drop you off and continue to a SELF central recharging car park they can continue to the next customer (Tesla & Uber’s visions) and will return by your smart phone App instructions. With the roads cleared of parked cars and vans, streets will be more environmentally and child friendly. To save the planet and the trees consider not to dig up the UK to lay more EV Cables. The existing UK Fuel stations and garages infrastructure provide much needed support to private and company vehicle drivers, passengers , employment and valuable revenues supporting UK business, not until most cars in the distant future are all electric the car manufacturers and fuel companies need to be given Big Tax incentives now to help support the huge investment required to preplace diesel and petrol engines with an alternative zero emissions fuel such as Hydrogen which would replace the fuel duty for the Governments Tax incentive support. This excellent article confirms fuel needs to be available immediately when required and in emergencies and expecting the UK Power generating companies to be able to replace every litre of fuel dispensed every day is an impossible ask there is a solution to this in the future and that is clean safe nuclear fuel technology with mini power stations installed locally to boost the electric capacity as being developed now by Rolls Royce the ultimate World Class British Brand for Engineering. PCA