From the rise to prominence of the hatchback in the 1970s (e.g. the Mark One Golf in 1975) through to the mid-2000s, the dominant bodystyles were hatchbacks for small/lower-medium cars and saloons for large/premium cars.

Over time, the dividing line became sharper: lower-medium saloons such as the Ford Orion died out, and Ford’s Sierra, launched initially only as a hatchback, morphed into the current Mondeo saloon. The only other choices for non-sports cars were estates (less than 10% of the total market) and the steady rise of what we used to call 4x4s. The 1970 Range Rover set off a slow-burn revolution – slow because many people could not see beyond the British Leyland quality problems to realise the full potential of the concept.

By the early 1990s, the Land Rover Discovery and the first European-spec Jeep Cherokee showed that the Range Rover concept could be expanded. Toyota then created the leisure SUV in the 1994 RAV4, and the segment started to grow significantly.

The car that added afterburners to the concept was the 2006 Nissan Qashqai, which offered an SUV outline to Nissan Almera buyers. Instead of an identikit hatchback on the drive, Mondeo Man and Worcester Woman could have something that looked to the neighbours like a smaller brother of those swanky Land Rovers and BMW X5s. The other benefit was the higher driving position – with increasing congestion and more speed cameras, you might as well get a decent view of what is eroding your driving enjoyment.

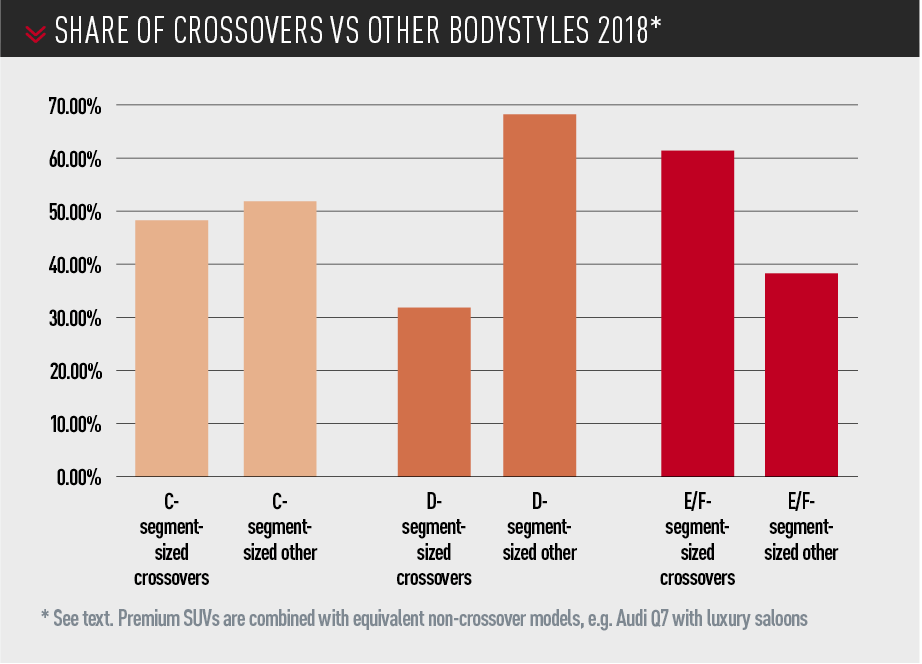

Today, crossovers and SUVs are on the verge of becoming the dominant bodystyle for all cars larger than superminis. In the C segment, crossovers such as the Qashqai took 42.8% of the segment last year, while hatchbacks and estates took 52.4%. However, there is another segment that has to be taken into account – premium compact crossovers. These are models such as the Volvo XC40 and BMW X1, which accounted for an additional 105,000 registrations, and are the same size as a Ford Kuga. If all C-segment-sized cars are combined, 49% are crossovers and 46.9% hatchbacks and estates. Given the growth rate of more than 10% a year for crossovers, 2019 is likely to see them take an absolute majority of sales in this category.

In the next category up, it is a similar story. Combining D-segment models, such as the Mondeo, with compact executive models such as the BMW 3 Series, gives a total market share of 7.6% (down from 9.5% in 2017). Market share of D-segment premium crossovers (e.g. BMW X3 or Volvo XC60) was 4.9%, up from 4.6% last year. The residual strength of long-term favourites such as the BMW 3 Series and Audi A4 means traditional models are putting up more of a fight in this category, but it seems likely that crossovers will nevertheless become the majority bodystyle within a few years.

In the next category up, it is a similar story. Combining D-segment models, such as the Mondeo, with compact executive models such as the BMW 3 Series, gives a total market share of 7.6% (down from 9.5% in 2017). Market share of D-segment premium crossovers (e.g. BMW X3 or Volvo XC60) was 4.9%, up from 4.6% last year. The residual strength of long-term favourites such as the BMW 3 Series and Audi A4 means traditional models are putting up more of a fight in this category, but it seems likely that crossovers will nevertheless become the majority bodystyle within a few years.

In luxury cars, that has already happened. The combined market share of traditional executive and luxury models, such as the Jaguar XF and Mercedes S-Class, was 3.7%. The share of luxury SUVs, (e.g. Land Rover Discovery, Range Rover), was 6.1%. Thus, luxury SUVs took 62.3% of combined sales. In fact, this was only a modest rise on 2017 (61.4%), indicating that luxury SUVs are so well established that there is less room for further market share growth (as discussed above, the luxury Range Rover set the template nearly 50 years ago, so these are the longest-established SUVs).

If the crossover bodystyle is going to dominate medium and large cars, the question arises – how far down the segments can it go? Could it become the leading design for superminis? B-segment crossovers currently account for 31.8% of the segment, up from 26% in 2017. In contrast, hatchbacks took a commanding 66.8% share in 2018. While crossovers can continue to grow, with important new models on the horizon, such as the Škoda Kamiq, second-generation Juke, and a Fiesta-based replacement for the Ecosport, they are unlikely to become the segment-leader any time soon. The supermini segment is exceptionally price-sensitive – after all, a significant proportion of customers are buying a supermini because they cannot afford a larger car. From the manufacturers’ point of view, the point of selling crossovers is that they have a better margin than hatchbacks – there is little point designing a crossover that has the same transaction price as a hatchback.

If the crossover bodystyle is going to dominate medium and large cars, the question arises – how far down the segments can it go? Could it become the leading design for superminis? B-segment crossovers currently account for 31.8% of the segment, up from 26% in 2017. In contrast, hatchbacks took a commanding 66.8% share in 2018. While crossovers can continue to grow, with important new models on the horizon, such as the Škoda Kamiq, second-generation Juke, and a Fiesta-based replacement for the Ecosport, they are unlikely to become the segment-leader any time soon. The supermini segment is exceptionally price-sensitive – after all, a significant proportion of customers are buying a supermini because they cannot afford a larger car. From the manufacturers’ point of view, the point of selling crossovers is that they have a better margin than hatchbacks – there is little point designing a crossover that has the same transaction price as a hatchback.

However, it is possible that hatchbacks will go back to the position they held in the early 1970s – dominant only in the B-segment (a class created by the first small hatchbacks, such as the Renault 5 and Fiat 127).

In medium-sized cars, hatchbacks with strong brands (the prime example being the Golf) will continue to thrive, but there will be a lot less room for “me-too” models. Twenty years ago, every mainstream brand had a C-segment hatchback because it was the centre of the European car market. Today, who would notice if Fiat, Renault or Citroën stopped marketing such models? Even the once-mighty Astra is looking vulnerable. The UK is traditionally Opel/Vauxhall’s largest market, but last year the Astra sold just 31,600 examples (down 36.1%), which was slightly fewer than the Mokka X, Vauxhall’s B-segment crossover. Fifteen years ago, total European Astra sales were 500,000 per year – in 2018, they were about 160,000.

In fact, the main opposition to crossovers is less likely to come from consumers than regulators. Intense pressure to reduce CO2 figures through the 2020s will make manufacturers wonder if adding bulk – to the detriment of both weight and aerodynamics – is really such a great idea. It will be interesting to see how consumers react to the pressure to make cars smaller again. There was a phrase in the skiing industry a few years ago, when skis started to change from long and narrow to much shorter and wider: “Once you go fat, you never go back” – people who bought their first wide skis never went back to narrow ones. Will crossover drivers be prepared to go back to hatchbacks? DAVID FRANCIS

Login to comment

Comments

No comments have been made yet.