If weather forecasts were made annually instead of daily, the current one would be along the lines of “Stormy 2019, expected calmer weather in early 2020, with a possible hurricane at the end of the year".

The 2019 car market finished at 2.31 million units, a 2.4% drop on 2018, which, at first glance, does not appear to be such a bad result.

However, it should be remembered that it represents a 14.2% drop on 2016 – a serious fall.

On the manufacturing side, the decline is worse: while the 2019 final figures are still to be published, the annual running rate in November was just 1.3 million. Back in 2016, more than 1.7 million cars were being made, and the industry was predicting a production figure of two million by 2020.

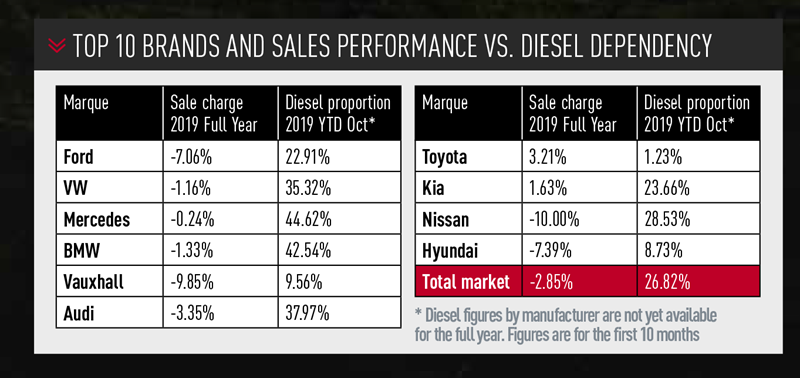

Within the car market, the trends were similar to recent years, but some of them have been slightly misunderstood. Diesel sales fell by 22% in 2019, and are down more than 50% since 2016, which has led a lot of people to assume that manufacturers who are particularly dependent on diesel are in trouble.

It is easy to think: “JLR made a record loss in 2018. It is diesel dependent (60% Jaguar; 80% Land Rover), so falling diesel sales are the problem”.

However, as statisticians like to say, “correlation is not causation”.

In fact, sales of diesel Range Rovers, and indeed BMW X/Audi Q models, have held up well, for the simple reason people still want large SUVs and petrol is a non-starter for most buyers.

JLR’s troubles relate to the Chinese market, low sales of Jaguar saloons and the failure of the “Does my car’s bum look big in this?” Discovery 5 (Answer: yes it does, in all possible colours and trims!). As the table shows, there is no link between car manufacturers’ dependency on diesel and their overall sales performance.

The trend towards crossovers and SUVs continues unabated.

One might have thought that they have become so ubiquitous by now that everyone would understand how they fit into the market, but a poorly-informed report from the UK Government-backed Energy Research Centre last month showed otherwise.

It claimed that SUVs, “emit a quarter more CO2 than a medium-sized car” and the rise of SUVs was one of the biggest causes of increasing CO2 emissions.

The report implies buyers of VW Golfs have been waking up and, bamboozled by cheap PCP deals, have moved into giant SUVs instead.

Of course, what has actually happened is that lots of buyers have moved from hatchbacks to crossovers within the same segment. A Golf buyer may have moved into a Tiguan, and a Corsa buyer may have moved into a Juke.

The people that have moved into X5s and Q7s are people that were previously driving 5 Series or A8 saloons.

It is the difference in CO2 between the hatchback/saloon and the crossover version of the same platform that matters – the difference between the Golf and the Range Rover is not the point. While there is a CO2 penalty for the taller crossover version, it is around 5% -10% - not the ludicrous figure of 25% implied by the report.

For example, the Renault Kadjar 1.3 TCe emits 5.5% more than the equivalent Megane, and the VW T-Roc 1.0 TSI emits 8.5% more than the equivalent Golf.

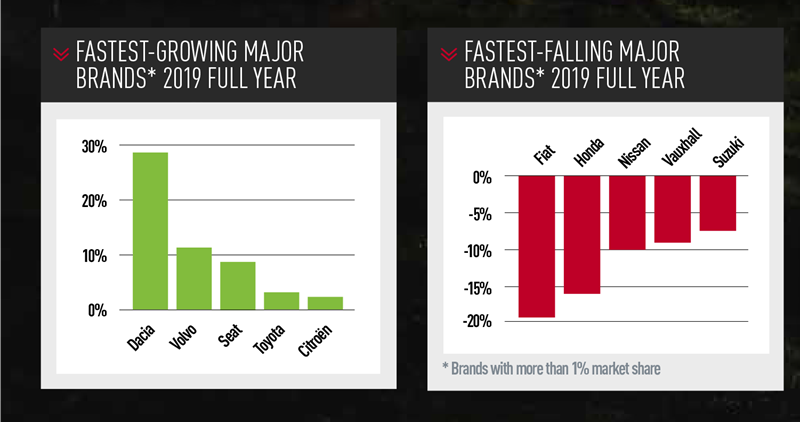

At a manufacturer level, premium brands continued to do well – at least those that could get their whole model ranges homologated to WLTP standards (unlike, for example, Audi).

The biggest change in this part of the market is the re-emergence of Volvo as a genuine premium brand, for the first time since the 1980s. For most of the past 30 years, Volvo has existed in no-man’s land, stuck between mainstream players and the increasingly dominant German trio of Audi, BMW and Mercedes-Benz.

Today’s Volvo crossovers, and even saloons, can go toe-to-toe with their German rivals. Volvo’s achievement is even more impressive when you consider what has happened to other would-be premium brands. Infiniti has been put out of its misery, DS has so far failed to sell much beyond its original DS3, and even Lexus, seen at its launch in 1990 as the one brand that could seriously damage the incumbents, has never passed 1% share.

One slightly surprising development, or rather non-development, which combines both SUVs and luxury brands, has been the modest impact of the Bentley Bentayga. It is still relatively early days but, so far, the new model has had virtually no impact on overall sales, despite Bentley originally talking about it doubling production to 20,000 per year.

Over at Rolls-Royce, the new Cullinan has only boosted UK sales by around 10%, although it is having more impact overseas. What role styling has played in this is an open question: one can look at successive generations of the Range Rover and decide it is pretty easy to design a luxury SUV, but one look at the Bentley and Rolls-Royce quickly demonstrates how hard it can be.

Looking forward to 2020, the industry’s future is once again out of its own hands. Assuming a deal with the EU to avoid future tariffs, the market is likely to drop approximately 5% to 2.2 million.

However, if there is no deal, the market is likely to drop sharply in the last quarter of 2020, with Citroën recently warning that a no-deal exit could eventually cut the UK car market by a further 25%. It is also worth noting that the current legal deadline for a deal is December 31, 2020 but, in practice, the deadline is September 2020.

This is because as a non-EU member, any deal with the UK will have to ratified by 27 countries plus a range of regional parliaments, a process which is expected to last three months. Yet again, the significance of any decisions made by UK car industry bosses in 2020 will be dwarfed by choices made in 10 Downing Street.

Login to comment

Comments

No comments have been made yet.