The concept of the driverless car is now firmly on the Government agenda and in the public domain. In July, the Department for Transport announced that driverless cars would be tested on UK roads by the end of this year. The UK announcement follows public trials in other parts of the world. The US is leading the way, with three states – Nevada, Florida and California – all having passed legislation allowing autonomous cars.

Although the idea of driverless cars is not new, it is only since 2000 that the technology has been available to make them viable. So far, Google has led the way with a prototype fleet of Toyota Priuses covering more than 300,000 miles on public roads. The initiatives have concentrated on adapting existing cars, although Ford, BMW, Audi and Volvo among others have started developments that could potentially lead to the production of specialised vehicles for the mass market.

|

||

|

Professor Jim Saker is director of the Centre for Automotive Management at Loughborough University’s Business School and an AM Awards judge. He has been involved in the automotive industry for more than 20 years. |

||

One of the most significant pieces written on the subject was published on November 25 in the New Yorker magazine headlined ‘Auto Correct – Has the self-driving car at last arrived?’ The author, Burkhard Bilger, starts by berating the current state of driving by saying that “human beings make terrible drivers. They talk on the phone and run red lights, signal to the left and turn to the right. They drink too much beer and plough into trees or veer into traffic as they swat at their kids… Of the 10 million accidents that Americans are in every year, nine-and-a-half million are their own damn fault.” He argues in support of the technology, quoting Google’s product manager for autonomous driving, Anthony Levandowski, who says the Google car drives more defensively than people do, rarely coming within two seconds of the car ahead.

Levandowski argues that the fear of the driverless car is irrational. “Once you make the car better than the driver, it’s almost irresponsible to have him there,” he says. “Every year that we delay this, more people die.”

The driverless car presents a number of challenges to our industry. If the autonomous car does take off, there are big issues about liability and insurance. If a driverless car can never be responsible for a crash unless the technology fails, will it be the manufacturer who is liable or potentially a dealer who services the vehicle?

As these cars are introduced, we will have a mixed economy on the road, with some vehicles human-driven and others not. The assumption will be that the driven cars will be the accident-causers and insurance premiums will rise.

From a dealer perspective, the driverless car could potentially be programmed to dutifully turn up for its regulation service whether the ‘passive driver’ wanted it or not.

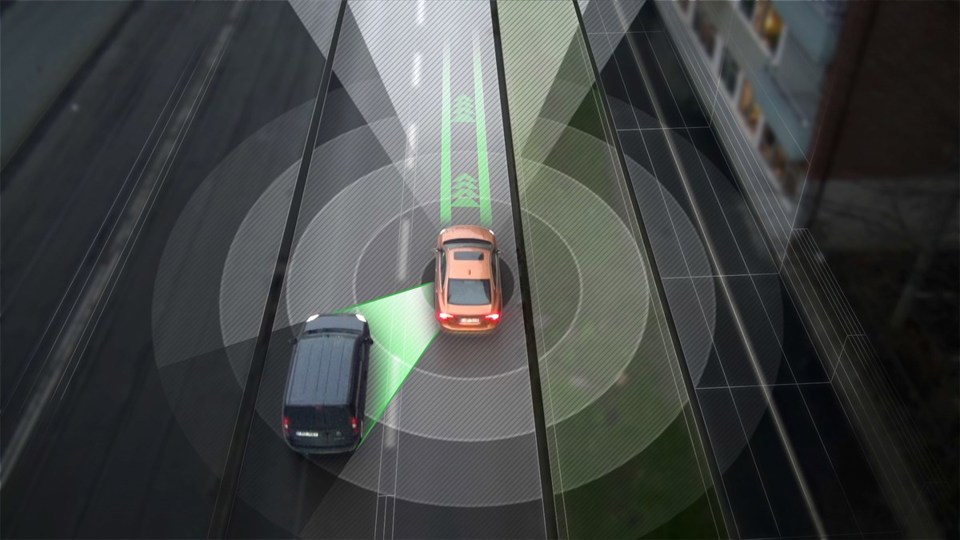

The technology exists and some of it is already available in the UK, with a number of the upmarket brands offering cars with collision avoidance technology and automatic braking. The automatic parking of cars has been available for some time on mid-range vehicles.

The difficulty with the concept is the rationale behind the Government thinking. They see it as a way of improving safety, but also reducing congestion. This is the part I don’t understand. By having safety-first cars all leaving the same distance between each other, the need for more roads will be inevitable. Traffic flows would slow to allow for greater margins of error. One of the ways in which our cities continue to move is by people making decisions to take alternative routes to avoid congestion. I am sure that a computer is quite capable of plotting an alternative route, but if it relies on the current level of satellite navigation technology linked to postcodes I fear we could all end up in cul de sacs with the autonomous vehicle refusing to turn around. Humans have a capacity to adapt that computers do not.

The adaptability and ingenuity of human driving struck me forcibly on a recruitment trip to India. It was the emaciated cow staring at me through the taxi window that finally convinced me I had no idea how anybody survives driving in the sub-continent. The rules of engagement seem to be that you give way to anything bigger than you and that priority is given to the thing in front of you, however it got there.

Red lights at junctions appear to be a suggestion that you may think about stopping as opposed to actually coming to a halt. The constant hooting and the strange road positioning of the myriad auto-rickshaws impact on the senses in a way no other traffic environment does. You have vast numbers of vehicles of all shapes and sizes squeezing their way along roads that seem to have no lane discipline. Some cars appear to be travelling on the wrong side of the road, while others avoid congestion by driving along the pavement.

Driverless cars may be the future of motoring in the long term, but I suspect by comparison with the wide highways of California, Google may find Friday night on the M25 or the traffic near the India Gate in Delhi to be a bigger challenge.

CGH - 08/01/2014 17:05

This article fails to mention the major threat to repairers: How will they cope when they can't blame the fault on "driver error" any more?