A decade that started with a deep recession has presented businesses with its fair share of challenges.

The recovery from that recession and the degree of stability since was delivered by a strategy based around the reduction of interest rates to the lowest in living memory. Political and economical uncertainty have ensured that they stayed low.

How have car retailers reacted to the longest-ever period of “cheap money”?

AM’s analysis of debt in the AM100 has identified some trends that may surprise, and lead some banks to see the motor industry in a more favourable light.

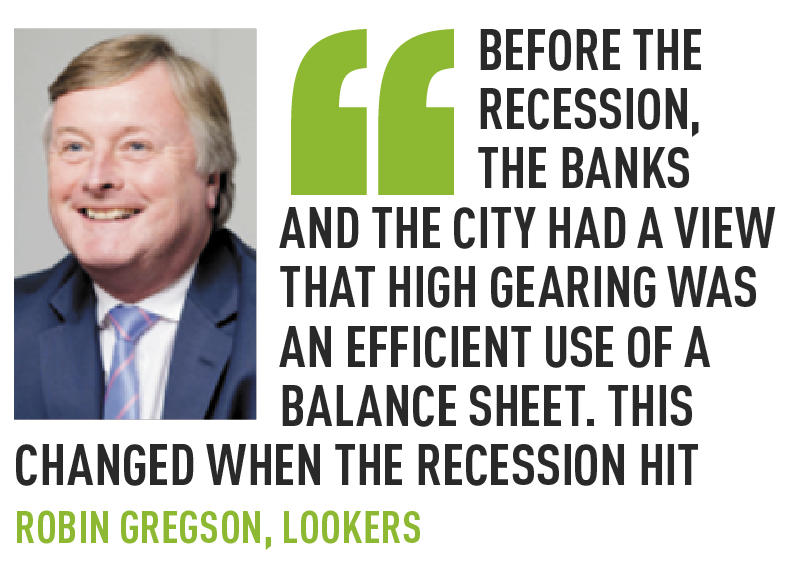

Robin Gregson, Lookers’ chief financial officer, summed up a path typical of the AM100’s larger groups.

“There is not the appetite for high levels of debt, even though interest rates are so much lower,” he said, remarking on the irony of the situation, given the high gearing seen when interest rates were higher prior to 2008.

The availability of such “cheap money” for so long could have lured many businesses into a borrowing culture to feed their growth. Gearing is one measure that sheds light on how car dealers have chosen to manage their finances – in particular, their debt.

Gearing can be calculated in a number of ways; AM uses the ratio of debt to equity as a percentage. So £100 of debt and £100 of equity equals 100% gearing. (Alternatively, you could calculate gearing as the ratio of debt to total capital, in which case the result would be 50%.)

Are smaller dealers at risk from too much debt?

Traditionally, gearing is considered an indicator of risk – the higher the level of borrowing, the higher the risk.

High borrowing accompanied by low equity is an even higher risk. Borrowing money has a cost attached, whereas equity, apart from dividend expectations, does not. Debt plus equity represents the capital of the business. The higher the proportion of debt, the higher the cost of capital.

So in a high-interest, high-uncertainty environment, you would expect businesses to try to reduce debt and rely more on equity, and vice versa in a low-interest, stable environment.

Of course, equity can be hard to come by, an increase in equity often resulting from retaining profits rather than distributing them in the form of dividends.

This latter strategy would be unpopular for larger businesses with external shareholders, who have invested with a view to a dividend yield, placing pressure on those businesses to expand while still maintaining dividends.

This inevitably means raising debt to finance acquisitions, build or refurbish premises, invest in equipment, systems, infrastructure etc.

The graph below shows the gearing percentage of 10 of the largest retailers versus 10 smaller retailers.

The samples are drawn from those businesses that have filed 2016 accounts, the larger 10 being drawn from the top third of the latest AM100, which have a turnover ranging from Perrys Motor Sales’ £652.8 million to Sytner’s £5.3bn, following its acquisition of CarShop.

The grouping of 10 smaller businesses is drawn from the bottom third of the AM100 – groups with turnover ranging from £130m to £200m.

For the larger businesses, the jump in gearing from 2007 to 2008 is what would be expected as they use the value of their business to borrow more in the face of financial difficulties prompted by the recession.

However, intriguingly, there is no comparable increase for the smaller businesses.

Were bankers more willing to live with the idea of debt financing losses for larger businesses, where they had a larger exposure in terms of the quantum of debt, than they were for the smaller borrowers?

What is also intriguing is that gearing fell back in 2009 for the largest businesses and then continued to fall – initially from about 120% to below 90% and then, by 2011, a little over 60% – despite the apparent low cost of finance and the low risk of that cost increasing.

Gregson said: “It is probably fair to say that dealer groups’ attitude to debt and gearing changed during the recession, but this is also true of many companies across the range of different sectors.

“Before the recession, the banks and the City had a view that high gearing was an efficient use of a balance sheet and this encouraged higher levels of debt.

“This changed when the recession hit and the banks were reducing their exposure where they had provided too much credit to the corporate world.

“Our attitude to gearing is that we would not want to have a ratio of net debt to EBITDA in excess of 1.5.

“We might accept a level slightly higher for the purpose of making an acquisition, but only if we could see this reduce in the short term to a level below 1.5.

“It is quite ironic that higher levels of gearing were acceptable when interest rates were much higher than the current level, but there is not the appetite for high levels of debt, even though interest rates are so much lower.”

“It is quite ironic that higher levels of gearing were acceptable when interest rates were much higher than the current level, but there is not the appetite for high levels of debt, even though interest rates are so much lower.”

Small dealers’ gearing grows

By contrast, for the smaller businesses, gearing fluctuated year by year, trending downwards until it reached below 80% in 2012, before heading back up to a point in the high 90s in 2016. This was the highest it has been since the immediate post-recession period of 2008/09.

Borrowing is often used to finance acquisitions. Since the larger groups have made significant acquisitions, you might have expected gearing to increase.

Additionally, there have been substantial demands for investment in new corporate identity and premises upgrades, which could also be expected to be at least partly debt-financed.

The rate of growth of both sets of businesses is roughly the same, so the contrasting change in gearing could mean that the investment requirements being driven by the national sales companies (NSCs) have fallen more heavily on the smaller businesses.

Gregson said Lookers had kept its gearing low by funding acquisitions through bank loans, which came with the proviso that cash generated by the group after the acquisitions have taken place was used to reduce the level of borrowings to an acceptable level.

He said: “This is best illustrated with our acquisition of Benfield, where the net debt-to-EBITDA ratio increased in the year of acquisition (2015) to 1.5, but had reduced significantly within nine months, by June 30, 2016, to a ratio of 0.7.”

James Mullins, financial director at Cambria Automobiles, said the group – 21st in the AM100 – is about to change its low gearing position in an attempt to meet manufacturer CI changes, enhance the operating capacity of the businesses and ensure greater stability in future.

He said: “Over the years, we have acquired less in fixed assets than we have generated in free cash flow and when we have invested it has come out of our cash reserves, keeping our gearing at a low level.

“Now our position has changed and we are about to make significant investment in new facilities to comply with various manufacturer requirements, including JLR’s Arch Concept, and also ensure our properties are freehold – freeing us from years of potential lease liability.

“Our gearing will change because we will be drawing on banking facilities, but we feel there are clear advantages.”

Cambria has five JLR sites and is currently in the process of redeveloping its Swindon site on freehold land.

A freehold site in Hatfield is awaiting redevelopment of its nearby JLR franchise and the group’s Aston Martin franchise will also be relocated to a freehold site in Solihull from its current, temporary, location.

Is pre-reg increasing debt?

Analysis of our data revealed that financing of stock also shows a disparity. The ratio of stock to debt for the larger businesses fell from 53% to 31%, but for the smaller businesses from 75% to 55%.

Again, perhaps the burden of financing pre-registrations appears to have fallen more heavily on the smaller groups.

Gregson said he thought it was unlikely that pre-registration would be more prevalent among smaller groups “unless they were not hitting their targets from normal trading and needed to pre-register to hit those targets”.

“We prefer to hit the targets from normal trading so that if we do pre-register it is our choice and only to achieve additional discounts to provide pre-registered cars at good prices.

“I would imagine this is similar in other of the larger groups and may explain the difference.”

Gregson said his group’s pre-reg volume was lower in the first half of 2017 than it was in the same period in 2016.

He said: “Another factor may be that the larger groups have wanted to reduce gearing in their balance sheets for the reasons noted above and perhaps there has not been the same desire to do this for smaller private companies, or perhaps their cash flow has not been sufficient to reduce the level of debt compared to the greater critical mass of the larger groups, which tend to have strong cash generation.”

Debt disparity? Yes. Danger? No

One measure increasingly used to demonstrate resilience is the relationship between EBITDA and net debt, as cited by Gregson.

EBITDA – earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortisation – is effectively the cash profit. In car retailing, EBITDA is substantial. A net debt to EBITDA ratio of 1:1 means the business generates enough cash to pay off net debt in a single year.

The second table, below, shows this ratio for the same two groups of AM100 businesses.

While the smaller groups are clearly in a less secure position than the larger groups, the ability to pay off all debt simply from cash resources in less than five years is an enviable position and a far cry from the position many businesses found themselves in back in 2008.

However, the rate of recovery following the 2008 crash was rapid and speaks volumes for the industry’s adaptability and resilience.

Furthermore, the impressive EBITDA data collated above does not include many of the more profitable smaller groups from within the AM100, simply because they have yet to file their 2016 accounts.

Bankers and investors take note – motor retail may be significantly more attractive than you think.

PIERS TRENEAR-THOMAS & TOM SHARPE

Login to comment

Comments

No comments have been made yet.